Ukrainian child went to a Finnish school – and started speaking Russian

Ukrainian language classes organized in the Help Center in Helsinki are one of the few options for children to maintain connection to Ukraine. PHOTO: OLENA VIRYCH / HELP CENTER OF UKRAINIAN ASSOCIATION IN FINLAND

Svitlana Yeharmina

Nadiia Fedorova

Published 29.10.2024 at 5:13

Updated 29.10.2024 at 11:02

Ukrainian Vira Boyko and her 8-year-old daughter, Maria, relocated to Finland after Russia’s full-scale invasion. Ukrainian is a Maria’s native language, but after enrolling in a Finnish school, she began speaking Russian.

“It’s not surprising,” Vira explains. “Maria went in an integration class where the teacher and most of the children speak Russian. So, she started using a language we didn’t intend for her to learn.”

For the Boyko family, it is essential to maintain connection with homeland and give to daughter a deep understanding of Ukrainian traditions and culture.

“We don’t know when or how the war will end. But we can preserve our identity to ensure our survival as a nation. This is impossible to achieve with the Russian language,” says Vira.

Satakieli is aware of dozens of similar stories. They come especially from families who have arrived in Finland from the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine.

After the Second World War, Russian has been the dominant language in these areas. Even the people whose first language was Ukrainian, were used to hearing and speaking Russian.

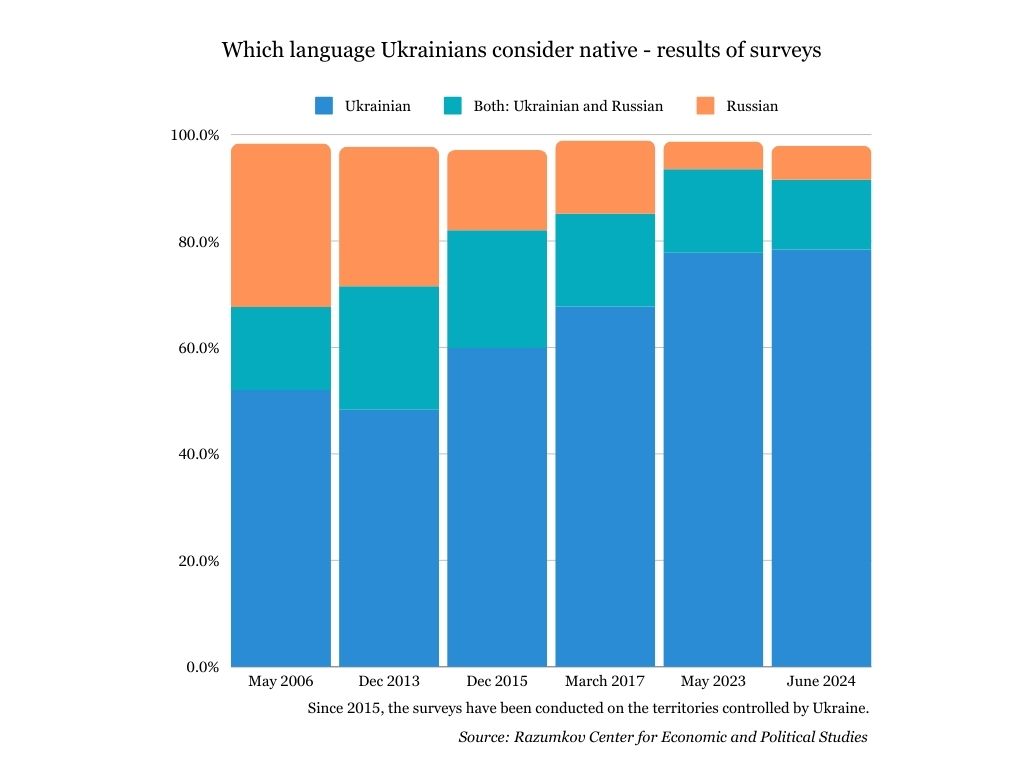

However, after the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, many families deliberately started to change their everyday language to Ukrainian. For them, it was a symbol for resistance to Russian imperialism and Kremlin propaganda.

In Ukraine, the change in language was supported by strong infrastructure: education, public services, media and leisure activities all available in Ukrainian.

But for those, who relocated to Finland, maintaining Ukrainian has proven to be a difficult task.

Strong presence of Russian language

When the main group of Ukrainian refugees arrived in Finland in 2022, they found themselves in a linguistically challenging environment.

There were of course Finnish and Swedish, at least one of which should be mastered for integration. Meanwhile, Ukrainian language infrastructure was non-existent. Instead, the newcomers were treated with surprisingly strong Russian-language network: schools, language training and activities for children.

Many parents found themselves in a difficult situation.

“Children’s clubs in Russian were the only option”, says Nadiia Maksymiuk, the lead coordinator of the Ukrainian Center in Finland.

“There was no Ukrainian alternative. The choice was between activities in Russian or nothing at all.”

The official data paints a misleading image

Over two and half years have since passed, but not much has changed. There are some efforts to create Ukrainian-language infrastructure in Finland, but the development has been very slow.

Russian language organizations assisting Ukrainians still receive significantly more support from the Finnish government than the Ukrainian language ones.

This is partly because of the status of Russian language in Finland. There’s been a Russian speaking minority in Finland for decades, and the cultural influence of the language is notable.

But the current situation is also affected by several misconceptions.

First of them comes from the official language statistics. According to official data, Russian is the largest minority language in Finland with over 99,600 native speakers in 2023. Meanwhile, there are officially only 26,500 native Ukrainian speakers – less than half of the number of Ukrainians living in Finland.

The issue is that the Finnish population registration system does not allow people to register two mother tongues. Many bilingual Ukrainians have registered only Russian and therefore have been automatically counted as part of the Russian-speaking population.

Another misconception is that Ukrainian and Russian speaking Ukrainians are thought to be two separate groups, which also need separate services, says Vassili Goutsoul, the Chairman of the Ukrainian Association in Finland.

This stereotype is often reinforced by Russian propaganda that claims Russian speakers would be persecuted in Ukraine. Denying the status of the Ukrainian language has been part of Russian repression for several hundred years.

In reality only 0,5 percent of the Russian speaking Ukrainians say that they do not understand Ukrainian.

Lack of government participation

Maintaining Ukrainian skills of the refugees should also be of interest to the Ukrainian government. Language skills will be needed, should the refugees return home after the war. In Ukraine, education, as well as all public services, are provided in Ukrainian.

Despite this, Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine has done little to improve the situation. There is no active cooperation with international educational institutions. The ministry currently only suggests studying Ukrainian online through free platforms.

Preservation and promotion of Ukrainian language in Finland remain on the shoulders of Ukrainian organisations and associations. They organize events and activities both for adults and children. However, their resources are very limited, and the activities concentrate on the largest cities.

Individual citizens, such as Vira Boyko are doing what they can.

Boyko has ordered Ukrainian books from Ukraine and ensured that her child has cartoons, films and social media channels in Ukrainian at her disposal.

Every Sunday Boyko drives almost 110 kilometres to Helsinki and back to take Maria to a Ukrainian-language children’s club. In Loviisa, where Boyko lives, there are no such activities.

Persecution of the Ukrainian language and culture

During the Russian Empire

1720: Peter I prohibited the printing of books in Ukrainian at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra.

1786 : Catherine II mandates educational institutions in Ukraine to switch to the Russian language.

1863: The Valuev Circular prohibits the publication of educational and religious books in Ukrainian, claiming that a separate “Little Russian language” does not exist.

1876: The Ems Decree of Alexander II bans the printing of Ukrainian books and the staging of theatrical performances in Ukrainian.

In the Soviet Union

1920s–1930s: Mass repressions against the Ukrainian intelligentsia occur in Ukraine. Approximately 300 prominent cultural figures are killed, causing significant harm to the country’s cultural development.

1932-1933: The Holodomor – a man-made famine that leads to the deaths of millions of Ukrainian peasants. This also weakens the Ukrainian linguistic environment and affects cultural identity.

1940s-1950s: Russification intensifies, especially in the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. The Ukrainian language undergoes editing to align it more closely with Russian.

1950s–1980s: Ukrainian teachers face discrimination in the form of significantly lower salaries and limited career opportunities compared to Russian-speaking teachers. This leads to a decline in the prestige of the Ukrainian language, which becomes associated with lesser education, while the Russian language is considered more “prestigious” and “scientific.”

Recent Events (since 2014)

2014: Russian propaganda uses the language issue to justify the annexation of Crimea and the involvement of its military in the war in Donbas. In occupied Crimea and the gray zone in Donbas, Ukrainian schools are being closed, creating a completely Russian-speaking environment.

2022: According to the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, over 200 schools have been destroyed, and 1,600 have been damaged. The Ministry of Culture reports the destruction of more than 1,000 cultural heritage sites. According to Human Rights Watch, the Ukrainian language is being eradicated in occupied territories, with threats made against education workers who refuse to switch to teaching in Russian. In schools in occupied territories, the occupying authorities promote anti-Ukrainian propaganda.